-

Join 91 other subscribers

-

Recent Posts

- Is Most Engagement “Inauthentic?”

- The Downside of Transparency: An Interview with Professor Eric Eisenberg (Part 2)

- Openness and Clarity are Overrated: an Interview with Professor Eric Eisenberg (Part 1)

- 2 Reasons to Use Numbers in Your Titles; and 2 Reasons to Ignore Anyone Who Does.

- Silence is NOT Golden

Archives

Categories

The Downside of Transparency: An Interview with Professor Eric Eisenberg (Part 2)

In the first part of our interview, “Openness and Clarity are Overrated,” Professor Eric Eisenberg re-made the case he had pioneered as a young communication scholar in the mid-1980s when he argued against the then prevailing view inside and outside of academia that clarity and openness were the primary criteria for assessing the effectiveness of communication. Instead, he suggested, and continues to suggest, that ambiguity and even selective disclosure could be important elements in successful organizational communications.

In this, the second part of our interview, Professor Eisenberg argues that strategic ambiguity is a necessary balance against the current demands for transparency, even while recognizing the ways in which the language of ambiguity, “plausible deniability” and selective disclosure has been used to mask ethical lapses, fiduciary irresponsibility and outright malfeasance.

Dr. Eisenberg is now Professor of Communication and Dean of the College of Arts and Sciences at the University of South Florida, author of over 70 academic articles (many of which were collected in his book, “Strategic Ambiguities,”) and is working on the 7th edition of his highly-rated textbook, “Organizational Communication: Balancing Creativity and Constraint.”

Our discussion took place at The Communication Leadership Exchange Annual Conference in Atlanta, Georgia in early May 2012.

Strategic Leadership Communication:

Your examples of ambiguity in political language [in Part One of the interview] raise the specter of those who have used ambiguous language to provide cover for unethical or even criminal behavior, for example, using the concept of “plausible deniability,” which allows various miscreants to claim innocence after the fact. Doesn’t the abuse of ambiguous language make the case for clarity, openness and perhaps even the radical transparency embodied in something like WikiLeaks?

Eric Eisenberg:

There’s no doubting the contemporary hue and cry for transparency (see, for example, leadership scholar Warren Bennis’ Transparency: How Leaders Create a Culture of Candor.) And for good reason. It’s very much a corrective against backroom dealings, lying and misrepresentation.

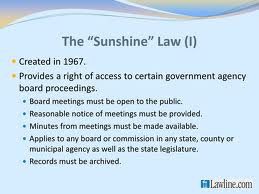

I can give you a very specific example from my own experience. In Florida, in the U.S., we have what is probably the most restrictive Sunshine Laws in the nation, which open up almost all state-supported activities to the public. So, when we [at the University of Southern Florida] do a search for a new president, or dean, or provost—a new leader for the university—all the meetings and all the notes are completely open to the public. Or when we put faculty up for tenure evaluation or promotion, the letters from those evaluating them are open to the candidates and potentially, even to the public.

That’s the kind of openness and transparency people have asked for, but in reality, it has all kinds of negative, paradoxical consequences. In our case, we’ve seen people stop speaking candidly in meetings; a lot of good candidates won’t apply for those jobs or withdraw their candidacy; and some people will refuse to write letters of recommendation if they have anything negative to say, making it hard to get honest appraisals.

Strict transparency inadvertently winds up highlighting an important need for strategic ambiguity: relational sensitivity. You don’t want to go on record as saying “X” about someone you know if you also know that everybody in the world is going to see what you have to say.

Strategic Leadership Communication:

It sounds as if you’re saying that the push to openness and clarity has had the paradoxical effect of increasing secrecy and silence?

Eric Eisenberg:

That’s exactly what I’m saying. It’s the equivalent of demanding that your partner in a marriage know everything about you because a healthy marriage is one where you have no secrets. But the fact of the matter is that’s not how human relationships work. A really healthy marriage, or any really healthy relationship has to have a balance between disclosure and protection, between expressing everything and protecting some confidences. In other words, between ambiguity and transparency.

Strategic Leadership Communication:

A last question on the concept of on strategic ambiguity: In my experience, most successful senior executives know when they need to be ambiguous. In their actual practice, they probably wouldn’t disagree with your statement that the “overemphasis on clarity and openness in organizational communication is… not a sensible standard or a widely held value against which to gauge communicative competency or effectiveness.” Nonetheless, an ethos of clarity in communication continues to exist at even the highest corporate levels. Why the strength of values and beliefs that equate clarity and openness with communication effectiveness, even when those values are not necessarily practiced?

Eric Eisenberg:

I think there are two separate things happening, and I think people conflate them; they put them together. The one thing that’s happening is that people really, really resent the abuses of power associated with secretiveness and obfuscation. As a consequence, every story in the news about an organization making some sort of ethical lapse or worse always propels people to say, “You know what? If you had a more transparent or open culture—a culture where other people knew what people were doing—this sort of thing wouldn’t have happened.” So that’s pushing from one side.

From the other side, you have an enormous amount of research and practical leadership experience that says that effectiveness in communication comes from saying just enough to make things happen, but not saying so much, or being so clear, that it forecloses all kinds of other possibilities and options.

Here’s an analogy that might help: strategic leadership communication—leadership communication that is effective—is more like giving someone a compass than it is like giving someone a map. Leadership focused on clarity is like giving someone a map: “Let me tell you the exact route to get from where you are now to where I want you to go.” The problem is that once you do that, people get passive, disengaged, or even resistant. They respond, whether overtly or not, by saying, “Wait a second. I got a brain in my head. What are you saying?”

And of course, if you lay things out with too much clarity and specificity, you run the risk of really being wrong. After all, a lot of the intelligence about what works in an organization doesn’t reside in the leader’s head; it’s widely distributed throughout the organization. If you don’t tap into that distributed intelligence, you increase the changes of making dumb, or at least difficult-to-execute decisions.

A leader who gives a compass on the other hand, says in effect, “Here’s the direction I want you to go in, and here’s the kind of metrics I’d like to see at the end. Now you go figure out the best way to chart your course.” That leaves the interpretive space for someone to make executing the strategy their own and to engage with it.

A leader who gives a compass on the other hand, says in effect, “Here’s the direction I want you to go in, and here’s the kind of metrics I’d like to see at the end. Now you go figure out the best way to chart your course.” That leaves the interpretive space for someone to make executing the strategy their own and to engage with it.

So, another paradox: too much clarity, too little engagement.

Smart leaders leave an interpretive space for people to be able to maneuver; they balance transparency with ambiguity. That balance is the hallmark of effective organizational communications.

2 Reasons to Use Numbers in Your Titles; and 2 Reasons to Ignore Anyone Who Does.

As I’m sure many of you do, I get feeds from web-based business news aggregators, like SmartBrief. What you get on a daily basis is an email with a bunch of headlines and links. If the headline is sufficiently compelling, you click on the link and read the article. That’s it.

The key for the aggregator is to make the headlines as compelling as possible so you’ll click through. How to do that? The answer seems to be this: use numbers!

Take a look at the following headlines, sent in one email, on one morning last week:

The Five Personalities of Innovators: Which One Are You?

5 Leadership Lessons from Capt Kirk

Business Etiquette: 5 Rules That Matter Now

The 5 Qualities of Remarkable Bosses

6 Habits of True Strategic Thinkers

The Five Big Lies about ‘Going Mobile’

How to Pay No Taxes: 10 Strategies Used by the Rich

Why use numbers? Two reasons immediately come to mind:

1. They connote credibility because they appear to be anchored in concrete reality. Let me give you an example of what I mean. A CEO with whom I did executive communications ran for Mayor of a large American city last year and I went to see him do a public, non-televised debate. While most of the content was fluff and most of the other candidates contentless, my former boss came across as much more grounded, real, credible. The way he did that was simple: in response to every question on any issue—education, budget, public services—he incorporated a number into his answer: “There are three things we need to do to begin to turn around our schools.” “Increasing economic development in the southern part of the city will require these three steps.” “If elected, I’ll immediately invoke a six-part plan to reduce the city budget deficit.”

His answers after the numbers weren’t all that different from the other candidates; they all sounded like clichéd, political rhetoric. But by incorporating numbers into his answers, the former CEO came across as having an understanding of the problem not shared by the others (after all, he knew the answer required three actions, not two, not four, three. So he had to know something, right?) His solutions seemed more real, and he seemed less… well, political, and therefore more credible than the others.

In the end, he was the clear winner in the debate, and is now Mayor.

2. They work. You’re reading this entry, aren’t you?

The need to process, add up or understand numbers generates a lot of unique activity in the brain. In fact, there’s apparently a distinct part of the brain believed to be involved in processing numbers: the intraparietal sulcus (IPS), located on the lateral surface of the parietal lobe.

The point is not to find it’s location, or even to pronounce it correctly, but rather simply to note that there is apparently a biological, brain-based basis for the way numbers “hook” us into believing that they are real and grounded in reality.

They work. It’s hard, if not impossible, to ignore their pull.

That’s their advantage. But also our problem. Anything that works so potently is bound to be exploited. And numbers are, to our detriment. In fact, there are at least two good reasons to ignore any headline with numbers altogether:

1. Most headline numbers are totally arbitrary; their only purpose is to grab your attention and make the headline sound scientific, real. In fact, they’re total fantasy. Take a look at those headlines above, for example: “5 Leadership Lessons from Captain Kirk.”

Putting aside the question of whether there are any leadership lessons to be gleamed from Captain Kirk, why 5 lessons? Why not 4? 6? 3? 7? The number itself is completely arbitrary. Or, “The Five Big Lies about Going Mobile.” Are there only “five” big lies? Not 6? 7? 10? Would the sixth lie about going mobile automatically be a “small” lie because it is not one of “The Five Big” ones? Utterly arbitrary. Completely made up by the author to attract your attention. Which leads to the second reason to avoid headlines with numbers in them:

2. You’re being manipulated. Not always, but often. Take these statements:

- Since 1948, whenever Socialist administrations were in power in France, gross national product grew at a rate 6.2% slower than when non-Socialist administrations were in power.

- In the last five years, the premium in return for investing in hedge funds rather than in index funds, after accounting for management and other fees, was only 0.0353%, barely a blip on the radar.

- Math and science scores for female students in developing countries have shown an average annual growth rate of 2.23% over the last 10 years. Scores for male students in developed countries have remained relatively static, with an overall decline in the same period of 1.89%. What does that say about development?

Take a second look at these statements. They could very easily be grounded, truthful, undeniable statements about reality. And maybe they are. But I wouldn’t know, because I made them up! The point here is not, as Mark Twain put it, “There are three kinds of lies: lies, damned lies and statistics.” Rather, it is that is people with “persuasive intent,” that is, people who are trying to sell you something—products, services, even politics and ideologies—understand the persuasive impact of numbers and use them manipulatively. They sound real, and you’re unlikely to take the time to track them down to their source to assess their validity. So you take them as true, whether they are or not.

***

Unfortunately, there is no getting around the ability of numbers to grab our attention and increase our gullibility. That’s what they do, pretty much automatically. Knowledge and awareness can help though, providing something of an inoculation.

The bottom line: when it comes to headlines with numbers, my best advice is: caveat emptor! Reader beware!

Silence is NOT Golden

I do a relatively frequent amount of public speaking, with one of most consistently requested topics being—no surprise—Strategic Leadership Communication. My presentation on the subject, titled, “Five Simple Rules: What Leaders Need To Know About Strategic And Effective Communication, But Don’t Ask Until It’s Too Late,” makes its most basic point early on in the presentation. And in a very simple manner. After a series of mostly visual slides, I move onto a slide that is blank. The audience sees a pitch-black screen.

When the “non-slide” comes up, I look at the audience and act like I think there’s a visual up there, pausing for about 20 seconds. (20 seconds may seem short in the abstract, but try to stop talking in the middle of a conversation for 20 seconds and you’ll see that it can feel like an eternity.)

It may sound like I’m trying to be clever and “one-up” the audience, but in truth, I don’t fool anybody. Nor am I trying to. Because the punch line isn’t the blank slide. It’s the one that follows. It’s where I ask people in the audience what they were thinking during the silence, and provide some possible answers on the slide, like, “I’m too sophisticated for these kinds of gimmicks. Just make your point,” or, depending on the time of day, “When’s lunch?” or “I could use another cup of coffee!”

Sometimes, based on the list on the slide, we’ll vote to find the most common thoughts people had during the silence. It’s usually pretty obvious; most get that the blank slide was intentional. The key point, though, isn’t what any individual or group thought, but that everyone has some thought. None of them went into a Zen blank slate.

They all filled in the silence with some explanation that tried to make sense of it. The resulting insight: communication doesn’t end when you’re silent, it just lets others create your message! And during times of uncertainty in organizations, the messages people create and then project into the silence are most likely to reflect their doubts, fears and anxieties, not what you hope they’ll think. And quite often their message may not accord at all with the facts or reality of the situation.

The salience of this for those senior leaders who keep on delaying communication because they’re “not ready,” is obvious: communication is going on whether or not you’re ready, only others are creating your messages for you! I’ve actually seen cases where, by the time the most senior leader got around to saying something in the midst of an uncertain situation, no one believed them, because the fear-based rumor that passed for communication had become everyone’s perceived reality.

Of course, it’s a lot easier in my role as consultant to tell other people that they need to communicate into the silence (even if it’s only to say you have nothing to communicate,) than do it myself. This is especially true in the blogosphere, where quantity, even more than quality, is necessary if one is to have even the faintest hope of “top of mind” awareness.

This was all brought home to me this week. After a fairly long, blogless stretch, due mainly to an intense work period, I received a bunch of notes from readers, colleagues, etc., inquiring if I was okay. Was something was wrong? Was I ill?

They were filling in the silence of my blog with their concerns about a worse case scenario for me. (By the way, thanks to those of you who checked in; everything’s fine!)

I hate to prove myself right by being wrong, but there it is. The lesson to me: between the relatively long, deeply thought out and researched entries, it’s important to continue the conversation. Even with short, simple notes. Like this one.

Okay. Done.

3 Ways Senior Leaders Can Support “Meaningful” Work

A friend and former colleague of mine is the Senior Vice President, Human Resources, at a biotechnology products and services company – that is, one of those companies racing to create gene sequencing machines that can bring the price of having one’s genes sequenced under $1,000. Even more: working to make gene sequencing so inexpensive that in the not-too-distant future it will be a routine medical test, like a blood test, opening the way to the promise of personalized medicine.

My friend is about as good as it gets in HR. He’s got a Ph.D. in Organizational and Industrial Psychology, a stellar work ethic, a strategic mindset, a consistent history of producing results everywhere he’s been, and, as hard driving as he is, an ability to generate loyalty and high performance from those who work for him. In other words, when it comes to senior HR officials, he’s a rare bird, indeed. Among the best of the best.

Not surprisingly, word has gotten around about him among headhunters, and he’s constantly getting calls dangling in front of him from the top HR position at much bigger, better known, and seemingly more prestigious companies. And with higher salaries and more stock options. But he has only one word for them: “No.”

Why not? “Because this company’s technology is going to save thousands and thousands of lives, and change the quality of life for millions and millions of people. Because I am part of changing the world for the better, and more money or stock options won’t make another company more meaningful than that.”

***

Teresa Amabile is the Edsel Bryant Ford Professor of Business Administration and a Director of Research at Harvard Business School. She has spent upwards of thirty years studying what she calls “the psychology of everyday work life,” [1] as well as what makes workers creative and innovative, and what motivates them to higher levels of performance.

She’s recently been publishing and publicizing[2] the results of a multi-year research study on creative work inside businesses. As a result of “an exhaustive analysis of the diaries kept by knowledge workers,” she discovered something she calls the “progress principle.” As Amabile describes it, the progress principle is that “Of all the things that can boost emotions, motivation, and perceptions during a workday, the single most important is making progress in meaningful work.”[3]

The focus on “progress“ in the “progress principle“ is obviously central. But it is only one half of the equation. The other half: the necessary meaningfulness of the work on which progress is being made. Or as Amabile puts it, “Making headway boosts your inner work life, but only if the work matters to you.”[4]

***

What my friend and Professor Amabile have in common is their understanding of the power of work that is meaningful. When workers believe that the work they are doing matters, they’re more committed, productive, innovative, and high-performing. And their businesses are more profitable.

Which raises the question relevant to this blog: what accountability do senior leaders have for the “meaning” given to their work by their employees? Some leaders might suggest that the answer is “none!” After all, isn’t it the case that meaning is in the eye of the beholder? That what is meaningful work to you might have no meaning for me? So how can this be the responsibility of a senior leader?

Amabile believes senior leaders can impact meaning at work. Generalizing from her research sample of senior leaders, however, she seems to think that they are as likely to destroy meaning for their employees as they are to support it – so much so that she titled a recent article, “How leaders kill meaning at work.”[5]

But that hasn’t been our experience. What leaders can do, and in my opinion, should do, is to create a context or framework within which workers can connect to meaning. What does that mean? Here are three ways that senior leaders can enhance the meaningfulness of employees’ perceptions of their work:

1. Create an emotionally resonant context for work. Let’s start with a generic example. Think of the least meaningful work you can imagine. How about something like digging ditches, or shoveling sand, the kind of unskilled manual labor that seems more appropriate to prison labor gangs than to anyone else. Hours of backbreaking labor. How high is this likely to rank on the meaningfulness scale? Pretty low.

But now add an emotionally resonant context to the work: the sand and dirt being shoveled and dug up is being taken to river banks where it will be used in sandbags designed to prevent the imminent flooding of a major metropolitan area. Without this work, lives may be lost and millions and millions in damage will disrupt the lives of the city’s innocent residents. Meaningful work? Might you be inspired to work a little longer and a little harder?

The point is not that digging ditches is inherently meaningful, or that leaders should make up stories or exaggerate the uses of their employees’ work. Rather, it is that meaning is not an inherent quality of the labor itself, but resides in our understanding of it. Change the emotional context, and the same work takes on a different, richer, more powerful meaning.

2. Provide a broader framework for understanding the work. One would think that working in one of the restaurants of a national pizza chain would be a hard place in which to find meaningful work. After all, when high paying professional jobs are about to be outsourced overseas, fast food jobs are often held up as the essence of the meaningless work that will remain.

Maybe so. Those jobs will certainly not reach the pay scale of technical or professional labor. But that doesn’t necessarily make them meaningless. In fact, I’ve seen them framed in an entirely different way.

Another friend and former colleague is now president of a national restaurant chain and a member of the Board of Directors of one world’s most renowned entertainment brands. For him, working in the restaurant business isn’t meaningless at all, and never has been, even when he started as “low-paid labor.”

For him, food is the “stuff of life” (and to everyone else, for that matter), and serving it a noble cause. And pizza, in particular, played a very special role. “You’re not in the fast food business,” he would consistently tell employees at the national pizza chain where we both worked, “but in the business of bringing families and friends together, of creating opportunities for people to share with each other, and in doing so raising the quality of people’s lives.”

Overstated? Not to him. And while it’s true this framework for making and delivering pizzas didn’t send tens of thousands of his employees into rapturous delight, it did provide them with a broader, richer framework for what most of them thought of as mundane work. And it made it easier for them to understand the “why” behind strategic initiatives to improve product quality and customer service. They did, and both improved.

3. Invoke a powerful legacy. Two words: Steve Jobs. Many, including me[6], have questioned whether Jobs’ abysmal treatment of employees was necessary for his success. The better question may be why so many employees stayed with him despite his subjecting them to ongoing verbal abuse and constant humiliation? The obvious answer is that it was a cost they were willing to pay to be part of creating something that they believed could change the world, something bigger than themselves.

That this was something Jobs understood very well and may have used manipulatively is beside the point (most famously in recruiting John Sculley from PepsiCo, when Jobs asked Sculley whether he wanted to spend the rest of his life selling “sugar water” or “come with me and change the world.”) A better measure of the impact of invoking a powerful legacy is the number of employees who look back on their efforts with pride, despite the difficulties of working with a very difficult boss.[7] Or more: sign up with that boss again for another potentially “world-changing” product.

The bottom line: Leaders can provide a framework that makes it easier for employees to perceive their work as meaningful. But too few of them do. To do so, they must first see it as part of their job. And second, they have to master the basics of strategic leadership communication: the elements of which have been the essence of this blog.

[1] Amabile’s Harvard faculty bio can be found here.

[2] Published in the book, The Progress Principle: Using Small Wins to Ignite Joy, Engagement, and Creativity at Work. See also her Harvard Business Review article, “The Power of Small Wins.”

[3] See “The Power of Small Wins,” p.72

[5] “How leaders kill meaning at work,” McKinsey Quarterly, January 2012

[7] This comes across strongly in Walter Isaacson’s excellent biography, Steve Jobs.

Lessons from “Three Non-Leadership Lessons from the Life of Steve Jobs”

The last Strategic Leadership Communication blog entry, “Three Non-Leadership Lessons from the Life of Steve Jobs,” generated more comments than any other entry yet – mostly positive and most sent as personal notes to me. A couple of resulting observations:

First, the adulation showered on Steve Jobs’ after his death would appear to be generating a backlash, particularly among people who read Walter Isaacson’s biography, Steve Jobs. Many of the comments we received had an “it’s about time someone said this” attitude, and were perhaps overly enthusiastic in that regard.

Apparently, people really resent hearing so many positive words about someone who so often treated people so miserably. The underlying assumption appears to be that we expect those who have been hailed as great leaders to be great people as well. And it is discomfiting when they’re not.

Apparently, people really resent hearing so many positive words about someone who so often treated people so miserably. The underlying assumption appears to be that we expect those who have been hailed as great leaders to be great people as well. And it is discomfiting when they’re not.

For better or worse, however, greatness as a leader and greatness as a person are orthogonal characteristics, that is, they vary independently, and are relatively uncorrelated. One doesn’t preclude the other. But neither does one necessitate the other, no matter how much we wish that were the case, or try to twist the facts to make that the case.

In Jobs’ case, the facts of his poor behavior were well-documented and indisputable. Ergo, the resentment toward the adulation Jobs has received, and the enthusiasm toward my somewhat debunking blog entry.

Second, the very need to have written the entry is at least partly necessitated by the strong confusion between correlation and causality often associated with leadership studies. As I mentioned in a footnote to the entry, ten years ago the leader to emulate was the “Level 5″ leader, who embodied “personal humility.” Not someone who would ever be mistaken for Steve Jobs!

As discovered and described by best-selling business author and professor Jim Collins in his book, Good to Great, the Level 5 leader:

- Demonstrates a compelling modesty, shunning public adulation; never boastful.

- Acts with quiet, calm determination; relies principally on inspired standards, not inspiring charisma to motivate.

- Looks in the mirror, not the window, to apportion responsibility for poor results, never blaming other people, external factors, or bad luck.

The idea of the “humble leader” had cultural resonance at the time, coming as it did at the end of the era of the heroic, star CEO, too many of whom had become monomaniacal destruction machines (a la Tyco’s Dennis Kozlowski, Enron’s Jeffrey Skilling, MCI-WorldCom’s Bernie Ebbers, etc.). Collins’ offering brought a breath of fresh air and hope to our view of leadership, and quickly became the new paradigm.

The idea of the “humble leader” had cultural resonance at the time, coming as it did at the end of the era of the heroic, star CEO, too many of whom had become monomaniacal destruction machines (a la Tyco’s Dennis Kozlowski, Enron’s Jeffrey Skilling, MCI-WorldCom’s Bernie Ebbers, etc.). Collins’ offering brought a breath of fresh air and hope to our view of leadership, and quickly became the new paradigm.

Unfortunately, Collins’ results embodied the correlation/causation confusion. His method had been to look at the leaders who had led their companies from “good to great,” and search for common characteristics among them. What he found was that those leaders all shared a strong sense of personal humility along with a terrific, disciplined focus.

Yet if those characteristics of leaders were alone enough to insure that companies would move from good to great, how to explain Steve Jobs, who had terrific focus, but little humility, and certainly moved a near-dead Apple to greatness? (Or Jack Welch, for that matter, with GE?) And did those same Level 5 leaders somehow lose their humility and focus as the performance of so many of Collins’ “great” companies declined from great to good, or even to mediocre-to-poor? The cause, then, must lie elsewhere.

The point is that neither modesty nor immodesty, humility or its lack, is any guarantor of quality leadership. And our obsession with seeking out the specific traits correlated with the success of a particular leader or group of leaders, whether Steve Jobs, or Collins’ “Level 5” leaders, and generalizing them as the key ingredient to a company’s success, may make us feel good, but ultimately has very little value in explaining a company’s success – hundreds of useless, semi-readable leadership books notwithstanding.

Three Non-Leadership Lessons from the Life of Steve Jobs

The untimely death of Steve Jobs, amidst the astonishing success of Apple, resulted in an enormous, effusive and understandable outpouring of worshipful praise for him and for his leadership. He was celebrated for his genius by the Technorati, mourned around-the-world by Apple acolytes and users alike, and hailed by global leaders as a peer to 20th century industrial giants Henry Ford and Thomas Alva Edison.

In this context, it may seem disrespectful, if not downright heretical, to question Jobs’ leadership capabilities. But I would like to suggest first, that, wrapped as he is in a haze of glory, it’s far too early to objectively assess his leadership; and second, that the most immediate and obvious lessons one can assuredly take away from his life are what not to do as a leader.

In this context, it may seem disrespectful, if not downright heretical, to question Jobs’ leadership capabilities. But I would like to suggest first, that, wrapped as he is in a haze of glory, it’s far too early to objectively assess his leadership; and second, that the most immediate and obvious lessons one can assuredly take away from his life are what not to do as a leader.

First things first. At the present moment, objectively assessing Jobs’ leadership without bias is made inordinately difficult by the “halo effect”. Professor Phil Rosenzweig, author of The Halo Effect and Eight Other Business Delusions describes the difficulty this way: “A successful company with a strong record of performance? The leader appears to be visionary, charismatic, with strong communication skills. A company that has suffered a downturn? The same leader appears to be hesitant, misguided, or even arrogant.”[1] In other words, it’s too early to tell whether Apples’ superior results were the result of Steve Jobs’ great leadership, or whether the appearance of Steve Jobs leadership being great is simply a result of Apples’ superior results.

One thing we can tell, aided by Walter Isaacson’s excellent biography, Steve Jobs, is that Jobs’ career offered a number of non-leadership lessons, including the three I briefly detail below.

One thing we can tell, aided by Walter Isaacson’s excellent biography, Steve Jobs, is that Jobs’ career offered a number of non-leadership lessons, including the three I briefly detail below.

Non-leadership lesson #1: If you treat people contemptuously, dismissively, manipulatively, lie to them, scream at them, even, on occasion psychologically abuse them, there’s no limit to the wonderful things they will do for you.

There’s no denying Steve Jobs’ singularity; he was brilliant, obsessively focused, visionary, innovative, demanding. He brought to bear a unique combination of technological sophistication, a Zen and Japanese inspired sense of the power of simplicity in design, and a vision that it was possible to create technically sophisticated, beautifully designed products for a mass market.

There’s also no denying that he was capable of treating people abysmally, including his own family, and often did so. The question is whether those two things were inextricably intertwined.

Too many people are going to commit the logical error of assuming the answer is “Yes.” After all, Steve Jobs was abusive, and his bio seems to imply that he couldn’t have achieved his brilliant successes, couldn’t have motivated his employees to the heights they achieved, if he hadn’t been.

The problem is that, while Jobs’ may have consistently treated his employees poorly, he didn’t consistently produce great products (is anyone still using a Next workstation? Where are the Apple evangelists mourning MobileMe?). In other words, his poor treatment of employees can’t account for the differences between his successful and unsuccessful products. Other factors, probably many of them, must be involved.

Moral #1: treating employees poorly is no guarantor of success; just because Steve Jobs’ did it, you don’t have to do it, too.

***

Non-leadership lesson #2: One way to ensure loyalty and commitment from your team is to take personal credit for all their successes, and blame them for all of your failures.

Jobs had the unsettling and upsetting habit of taking personal credit for all of Apple’s successful products, much to the dismay and frustration of the employees who were responsible for the innovation and had often done much of the work. And he was quick to find fault or failure in others for matters where at least some of the accountability belonged on his lap.

Someone who knew Jobs as well as anyone, one of the great loves of his life, suggested that this self-centeredness was as a result of Jobs suffering from Narcissistic Personality Disorder, which, she said: “…fits so well and explained so much of what we struggled with that I realized expecting him to be nicer or less self-centered was like asking a blind man to see.”[2]

Whether that diagnosis is accurate or not, the behavior remains. And while it seems self-evident that this quality can’t be said to cause product success, it’s also potentially worrisome that some may draw the lesson that such behavior is acceptable because “Steve Jobs did that and look how successful he was.”

Moral #2: Taking credit for the success of others, and blaming them for your failures is no guarantor of success, only of resentment.

***

Non-leadership lesson #3: It takes a charismatic leader, someone who can seemingly get anyone to do anything anytime anywhere, to create a company that is “built to last,” that is, can endure long beyond the lifetime of its charismatic leader.

There’s no doubting Jobs’ charisma: “Jobs could seduce… people at will, and he liked to do so.”[3] He had it all: enormous charm, an unnerving ability to stare without blinking which made people crack beneath his gaze, a seeming ability to deny reality and create his own reality and in doing so get people to go beyond their limits and do things they never thought themselves capable.

The question is whether charisma is necessary to build a great company that will last. The answer is… probably not, for a number of reasons:

First, charisma, by definition, is non-transferable. When the charismatic is gone, so is the charisma. Here is how Max Weber, the German sociologist who introduced the term “charisma” into the social sciences defined it: “a certain quality of an individual personality, by virtue of which he is set apart from ordinary men and treated as endowed with supernatural, superhuman, or at least specifically exceptional powers or qualities. These are not accessible to the ordinary person, but are regarded as of divine origin or as exemplary, and on the basis of them the individual concerned is treated as a leader.”[4] In other words, charismatic authority is embodied in the individual alone, rather than, say, the office, and is therefore not transferable. Steve Jobs’ charisma leaves Apple with Steve Jobs.

Second, charismatic leaders are as likely to create a corporate disaster as an enduring company. For every Steve Jobs, there is a Jean-Claude Messier, who was CEO of Vivendi Universal until he was forced to resign in disgrace, eventually leading to the sale of a huge chunk of the company to GE. Charisma can be productive or destructive: For every Mohatma Ghandi, there is a Rasputin, for every John Kennedy, there is a Jim Jones.

The point is that, while we won’t know whether or not Jobs’ has built an enduring company for quite a while[5], we can feel fairly comfortable asserting that if he has done so, it wasn’t solely the result of his charisma.[6]

Moral #3: charisma, by itself, is no guarantor of a company’s longevity; its positive characteristics must be translated into enduring values and principles, and institutionalized in processes, culture, etc.

***

There is no doubting Jobs’ genius, or the singularity of its vision. He had his faults, but even his faults often had their virtuous side. He was a perfectionist and obsessively controlling, but not as an end in itself, but at the behest of a set of values and aesthetic principles focused on creating user-centered, rather than technology-centered products, and product experiences.

There was no one quite like him. But that’s the point: it’s precisely his singularity that suggests his success cannot be easily imitated. Not that there won’t be those trying, and too often merely reproducing his vices rather than his virtues.

[1] “Misunderstanding the Nature of Company Performance: The Halo Effect And Other Business Delusions,” California Management Review, Vol. 49, #4, p.8

[2] Walter Isaacson, Steve Jobs, Simon and Schuster, 2011, p.266

[3] Isaacson, p. 312

[4] Max Weber, The Theory of Economic and Social Organization, translated by Talcot Parsons, Free Press, 1947, pp.358-359. Note: this book is available on Google books, and can be easily searched.

[5] As of this writing, Apple is the 10th most valued company in the world; its stock is riding at an astounding $420.30/ share. One measure of how independent Apple has become of Jobs’ charisma will be to check its value status and stock price in five years, say end of 2016.

[6] Five years ago, the leader to emulate was the “Level 5 leader,” who embodied “personal humility.” Not someone who would ever be mistaken for Steve Jobs. As discovered and described by best-selling business author and professor Jim Collins in his book, Good to Great, the Level 5 leader:

- Demonstrates a compelling modesty, shunning public adulation; never boastful.

- Acts with quiet, calm determination; relies principally on inspired standards, not inspiring charisma to motivate.

- Looks in the mirror, not the window, to apportion responsibility for poor results, never blaming other people, external factors, or bad luck.

Given the greatness of Apple under Steve Jobs’ at this moment, what are to we to make of the Level 5 leader paradigm? How quickly times, and leadership fads change!

Getting in Touch with Reality: Three Simple Suggestions for CEOs Who Want to Connect with their Front Line

In the last entry of Strategic Leadership Communication, we pointed out something probably self-evident already, and aptly demonstrated by the show Undercover Boss: those at the top are out of touch with the reality of those on the front lines. The important question is: what is to be done?

The good news is that there are answers, they’re not rocket science, and most of them are already in use. Here are three simple suggestions for CEOs who would like to know what the heck is actually happening on their front lines:

Suggestion #1. Go to them and ask.

Okay, this sounds simple to the point of ridiculousness. And conceptually it is. But doing it can be ridiculously hard, with CEOs enormously resistant to the idea. Why? For one thing, they think they don’t need the input and think they already know what’s going on (see the blog entry on power and persuasion for some context.) For another, it requires a not insubstantial investment of their most precious commodity: time.

Additionally, getting information out of front-line employees takes work. First, and foremost, you have to ensure that local managers haven’t filtered their employee selection so that you’ll only get to talk to employees that will tell you what their managers think you want to hear. Second, it can take real effort to elicit honest feedback from people who are likely to be so intimidated by your title and position that they’ll also try to tell you what they think you want to hear.

Nonetheless, many CEOs make it a habit to meet regularly with front line employees. How? Simple: They regularly incorporate into their schedule an informal meeting with front-line employees either at corporate headquarters or on a visit anywhere near one of their corporate locations. Here’s what that might look like:

- Breakfast meetings, or lunch (sometimes that might mean taking your lunch in the company cafeteria and simply sitting at some random table).

- Roundtables built into empty spots between meetings.

- Some end-of the day format. The CEO could join in an already scheduled activity. (I’ve seen a CEO have a beer with a bunch of employees.)

Content

- Spontaneous. The CEO simply asks what is on people’s minds. (Not recommended; the intimidation factor makes this risky.)

- Questions and Answers (with questions submitted beforehand directly to the CEO’s mailbox to make it both easier to ask, and harder to filter.)

- A prepared proposal/project/message/issues/set of questions that the CEO brings in order to receive feedback.

Participants

- Random selection.

- Local “influentials” as selected by local management; or you could have someone on your staff do a bit of research on influential front-line employees.

- Existing groups, like a first-level supervisor forum.

Process

- Guided discussion, with the CEO facilitating.

- Active listening.

Suggestion #2. Have them come to you.

This also sounds silly; who’s going to have front-line members of a global workforce travel to corporate headquarters on a regular basis? But there’s an already successful formula:

Create a council of front-line “influencers,” that is, front-line employees highly respected by their peers.

Form: Bring them together for a one-time only, face-to-face meeting with the CEO. From then on, have them meet via phone or videoconference on a monthly basis.

Content: Whatever issue needs input or reaction from the front lines. This group can serve as a focus group for testing out messages, plans, processes, etc. Its participants serve as both a source of information from their peers, and as a source of information to their peers, so information sharing is important.

Participants: This should be a diverse group of front-line employees to whom others listen. A sampling of local management will often surface the right person.

Process: This group can be run or moderated by your internal communication leader, with the CEO making a quarterly appearance, or simply providing a 5-minute charge to this group on a monthly basis. The CEO sets the agenda.

This works. It gets around most of the filters the keep CEOs out of touch with the front lines, and provides them with a direct link to influential front-line employees. Why doesn’t every organization have this?

Suggestion #3. Have someone else do it.

Most companies survey their employees on a regular basis, gauging their level of engagement in one form or another (e.g., many companies use the Gallup Engagement Survey, which is succinct, comparable, and offers trend data.) As an initial framework for understanding what’s going on at the front lines, surveys work.

But do employee engagement or culture surveys give you a sense for how feelings are running on your front lines? NO. Do they provide the context needed for gauging the impact of important decisions dependent on the front lines for execution? NO. They point to potential problems, but they need to be supplemented if you’re going to get at the texture and meaning of your survey results.

How to do this? Not easily. Investing in gauging the emotional texture and meaning of what’s going on with your front lines can be time consuming and expensive. But, if you’re engaged in a major change effort with serious business repercussions and need to enlist your front lines, it’s necessary.

What can be done? Here are some already suggestions that have already been shown to work:

Form: A series of focus groups and/or one-on-one confidential interviews.

Content: Driven by your most urgent business needs. But beware: developing the right interview schedule for this kind of discovery is both an art and a science. If you don’t want your effort to go up in smoke, we would recommend either an outside professional, or your marketing research group.

Participants: Probably randomly selected from impacted front-line employees.

Process: As noted, we suggest outsourcing the process to an independent firm or trusted advisor, someone who is:

- Not a direct report,

- Doesn’t have a vested interest in any outcome, and who

- Has built a relationship of trust with you.

As a rule of thumb for figuring out who should do this, I would avoid your Human Resources function, even if the lead HR person already has “trusted advisor” status with you. As a corporate function with whom all employees interact, HR professionals are likely to have a higher threshold if they are to achieve needed trust and credibility.

***

That’s it: three simple suggestions. As I said, this isn’t rocket science. Many, if not most CEOs already do at least one of these. Doing it is not hard. Deciding to do it is. But that’s another subject altogether.

Note: Strategic Leadership Communication wishes all of you a wonderful and wholesome holiday season, and a happy, healthy, and prosperous new year ahead.

Are CEOs in Touch with Reality? Uh…. Not Really.

A friend of mine works with a CEO who has appeared on the television show, “Undercover Boss,” (and who has been basking in the glow of his appearance ever since.) Given the positive corporate and personal publicity that resulted, it is certainly understandable why he, or any CEO for that matter, would want to participate.

It’s also understandable why the show has become so popular. For one thing, though not advertised this way, it does elicit a certain kind of satisfaction for viewers, Schadenfreude if you will, in seeing the “high and mighty” suffering the same humiliations frontline employees too often do. For another thing, it reinforces the ardent belief among front-line employees, bordering on wish fulfillment, that if bosses only knew what was really going on with them, they would change things dramatically.

It’s also understandable why the show has become so popular. For one thing, though not advertised this way, it does elicit a certain kind of satisfaction for viewers, Schadenfreude if you will, in seeing the “high and mighty” suffering the same humiliations frontline employees too often do. For another thing, it reinforces the ardent belief among front-line employees, bordering on wish fulfillment, that if bosses only knew what was really going on with them, they would change things dramatically.

While that belief may not actually hold true in reality, one thing is for sure: it’s always true on “Undercover Boss,” and always allows the CEO to turn hero at the end, dispensing justice, rewarding virtue, and righting all wrongs. Of course this suggests another reason for the popularity of the show: the satisfaction of seeing bad and incompetent supervisors and employees get their comeuppance, of revenge.

The one thing missing, as far as I can see, is that nobody ever seems to ask these bosses the obvious question underlying the show’s premise, “How can you have been so ignorant of what goes on in your own company?”

I’m being a bit disingenuous here. The idea that those on top might be out of touch with their frontlines is a veritable truism. It’s certainly not new news: Almost 40 years ago, George Reedy, former press secretary to U.S. President Lyndon Johnson, published, The Twilight of the Presidency, in which he argued that the isolation of the president behind a wall of protectors was undermining his ability to get the information he needed to understand what was actually happening in the world. That isolation, he suggested, was becoming a fatal flaw of the office.

While presidents of companies are not presidents of countries, I would suggest that the difference in regard to this issue is simply one of degree. Five years ago, I had the opportunity to ask a relatively new, large corporation CEO what had been his biggest surprise since taking on his role. His answer: how lonely and isolated the role was, and how difficult it was to get straight information.

The problem is enduring. Only a couple of months ago, The Economist reported on a Boston Consulting Group study, “National Governance, Culture and Leadership Assessment,” which showed that bosses continue to be out of touch with the reality of their own employees. The study found, as reported by The Economist, that:

“Bosses are eight times more likely than the average [employee] to believe that their organization is self-governing.[1] Some 27% of bosses believe their employees are inspired by their firm. Alas, only 4% of employees agree. Likewise, 41% of bosses say their firm rewards performance based on values rather than merely financial results. Only 14% of employees swallow this.”

The gap between the CEO’s and the employees’ perception of an organization is not necessarily the fault of the CEO. They cannot be everywhere at once. They have to rely on others to filter information for them to ensure they get only what’s most important and most relevant for their business success.

The fault, then, dear friends, lies not in our CEOs, but in those who filter the information to them, who, however honorable their motives, cannot filter out their own biases. The reality is that no one working for a CEO is totally disinterested, or can be totally disinterested. Whether wittingly or not, they filter information to suit their own views and interests. Even scientists, whose success presumably rests on their being professionally disinterested, are not immune from bias infiltrating their work. As research has shown, scientists have a hard time disentangling the conclusions of their research from the biases of their funding sources, particularly if their research is industry-sponsored (there’s even a term for it: “sponsorship bias”.)[2]

It’s also the case that some CEOs may, for at least semi-rational reasons, put understanding what’s going on at the front lines low on their list of priorities. After all, as far as I know, there is no direct, easily measurable, causal relationship between a company’s financial performance and discontinuities between leaders’ and employees’ understanding of reality on the front lines.

Finally, as the survey results reported in The Economist suggest, some CEOs may think they already know what’s going on with employees on their front lines, making extra efforts to find out seem superfluous. They are likely to be suffering from “optimism bias,” that is, the tendency to overestimate the outcomes of their actions (as in, something like 90% of drivers describing their driving as “above average.” Think about it.) It is well known to be particularly acute among those in power.

To put it simply, then, either CEOs don’t know what’s going on at their company’s front lines, don’t want to know, think they already know, or last, want to know, but no one will tell them.

For at least some of you, all of this is probably self-evident already: those at the top are out of touch with the reality of those who do the work on the front lines. The important question is: what is to be done?

The good news is that there are answers, they’re not rocket science, and most of them are already in use. In the next entry of Strategic Leadership Communication, I’ll offer leaders three suggestions for learning what’s actually going on with their front lines.

[1] Vs. either a “command-and-control” top-down culture, or “informed acquiescence,” that is, a “command and control” culture with smarter leadership than and some carrots mixed in with the sticks.