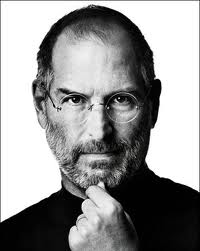

The untimely death of Steve Jobs, amidst the astonishing success of Apple, resulted in an enormous, effusive and understandable outpouring of worshipful praise for him and for his leadership. He was celebrated for his genius by the Technorati, mourned around-the-world by Apple acolytes and users alike, and hailed by global leaders as a peer to 20th century industrial giants Henry Ford and Thomas Alva Edison.

In this context, it may seem disrespectful, if not downright heretical, to question Jobs’ leadership capabilities. But I would like to suggest first, that, wrapped as he is in a haze of glory, it’s far too early to objectively assess his leadership; and second, that the most immediate and obvious lessons one can assuredly take away from his life are what not to do as a leader.

In this context, it may seem disrespectful, if not downright heretical, to question Jobs’ leadership capabilities. But I would like to suggest first, that, wrapped as he is in a haze of glory, it’s far too early to objectively assess his leadership; and second, that the most immediate and obvious lessons one can assuredly take away from his life are what not to do as a leader.

First things first. At the present moment, objectively assessing Jobs’ leadership without bias is made inordinately difficult by the “halo effect”. Professor Phil Rosenzweig, author of The Halo Effect and Eight Other Business Delusions describes the difficulty this way: “A successful company with a strong record of performance? The leader appears to be visionary, charismatic, with strong communication skills. A company that has suffered a downturn? The same leader appears to be hesitant, misguided, or even arrogant.”[1] In other words, it’s too early to tell whether Apples’ superior results were the result of Steve Jobs’ great leadership, or whether the appearance of Steve Jobs leadership being great is simply a result of Apples’ superior results.

One thing we can tell, aided by Walter Isaacson’s excellent biography, Steve Jobs, is that Jobs’ career offered a number of non-leadership lessons, including the three I briefly detail below.

One thing we can tell, aided by Walter Isaacson’s excellent biography, Steve Jobs, is that Jobs’ career offered a number of non-leadership lessons, including the three I briefly detail below.

Non-leadership lesson #1: If you treat people contemptuously, dismissively, manipulatively, lie to them, scream at them, even, on occasion psychologically abuse them, there’s no limit to the wonderful things they will do for you.

There’s no denying Steve Jobs’ singularity; he was brilliant, obsessively focused, visionary, innovative, demanding. He brought to bear a unique combination of technological sophistication, a Zen and Japanese inspired sense of the power of simplicity in design, and a vision that it was possible to create technically sophisticated, beautifully designed products for a mass market.

There’s also no denying that he was capable of treating people abysmally, including his own family, and often did so. The question is whether those two things were inextricably intertwined.

Too many people are going to commit the logical error of assuming the answer is “Yes.” After all, Steve Jobs was abusive, and his bio seems to imply that he couldn’t have achieved his brilliant successes, couldn’t have motivated his employees to the heights they achieved, if he hadn’t been.

The problem is that, while Jobs’ may have consistently treated his employees poorly, he didn’t consistently produce great products (is anyone still using a Next workstation? Where are the Apple evangelists mourning MobileMe?). In other words, his poor treatment of employees can’t account for the differences between his successful and unsuccessful products. Other factors, probably many of them, must be involved.

Moral #1: treating employees poorly is no guarantor of success; just because Steve Jobs’ did it, you don’t have to do it, too.

***

Non-leadership lesson #2: One way to ensure loyalty and commitment from your team is to take personal credit for all their successes, and blame them for all of your failures.

Jobs had the unsettling and upsetting habit of taking personal credit for all of Apple’s successful products, much to the dismay and frustration of the employees who were responsible for the innovation and had often done much of the work. And he was quick to find fault or failure in others for matters where at least some of the accountability belonged on his lap.

Someone who knew Jobs as well as anyone, one of the great loves of his life, suggested that this self-centeredness was as a result of Jobs suffering from Narcissistic Personality Disorder, which, she said: “…fits so well and explained so much of what we struggled with that I realized expecting him to be nicer or less self-centered was like asking a blind man to see.”[2]

Whether that diagnosis is accurate or not, the behavior remains. And while it seems self-evident that this quality can’t be said to cause product success, it’s also potentially worrisome that some may draw the lesson that such behavior is acceptable because “Steve Jobs did that and look how successful he was.”

Moral #2: Taking credit for the success of others, and blaming them for your failures is no guarantor of success, only of resentment.

***

Non-leadership lesson #3: It takes a charismatic leader, someone who can seemingly get anyone to do anything anytime anywhere, to create a company that is “built to last,” that is, can endure long beyond the lifetime of its charismatic leader.

There’s no doubting Jobs’ charisma: “Jobs could seduce… people at will, and he liked to do so.”[3] He had it all: enormous charm, an unnerving ability to stare without blinking which made people crack beneath his gaze, a seeming ability to deny reality and create his own reality and in doing so get people to go beyond their limits and do things they never thought themselves capable.

The question is whether charisma is necessary to build a great company that will last. The answer is… probably not, for a number of reasons:

First, charisma, by definition, is non-transferable. When the charismatic is gone, so is the charisma. Here is how Max Weber, the German sociologist who introduced the term “charisma” into the social sciences defined it: “a certain quality of an individual personality, by virtue of which he is set apart from ordinary men and treated as endowed with supernatural, superhuman, or at least specifically exceptional powers or qualities. These are not accessible to the ordinary person, but are regarded as of divine origin or as exemplary, and on the basis of them the individual concerned is treated as a leader.”[4] In other words, charismatic authority is embodied in the individual alone, rather than, say, the office, and is therefore not transferable. Steve Jobs’ charisma leaves Apple with Steve Jobs.

Second, charismatic leaders are as likely to create a corporate disaster as an enduring company. For every Steve Jobs, there is a Jean-Claude Messier, who was CEO of Vivendi Universal until he was forced to resign in disgrace, eventually leading to the sale of a huge chunk of the company to GE. Charisma can be productive or destructive: For every Mohatma Ghandi, there is a Rasputin, for every John Kennedy, there is a Jim Jones.

The point is that, while we won’t know whether or not Jobs’ has built an enduring company for quite a while[5], we can feel fairly comfortable asserting that if he has done so, it wasn’t solely the result of his charisma.[6]

Moral #3: charisma, by itself, is no guarantor of a company’s longevity; its positive characteristics must be translated into enduring values and principles, and institutionalized in processes, culture, etc.

***

There is no doubting Jobs’ genius, or the singularity of its vision. He had his faults, but even his faults often had their virtuous side. He was a perfectionist and obsessively controlling, but not as an end in itself, but at the behest of a set of values and aesthetic principles focused on creating user-centered, rather than technology-centered products, and product experiences.

There was no one quite like him. But that’s the point: it’s precisely his singularity that suggests his success cannot be easily imitated. Not that there won’t be those trying, and too often merely reproducing his vices rather than his virtues.

[1] “Misunderstanding the Nature of Company Performance: The Halo Effect And Other Business Delusions,” California Management Review, Vol. 49, #4, p.8

[2] Walter Isaacson, Steve Jobs, Simon and Schuster, 2011, p.266

[3] Isaacson, p. 312

[4] Max Weber, The Theory of Economic and Social Organization, translated by Talcot Parsons, Free Press, 1947, pp.358-359. Note: this book is available on Google books, and can be easily searched.

[5] As of this writing, Apple is the 10th most valued company in the world; its stock is riding at an astounding $420.30/ share. One measure of how independent Apple has become of Jobs’ charisma will be to check its value status and stock price in five years, say end of 2016.

[6] Five years ago, the leader to emulate was the “Level 5 leader,” who embodied “personal humility.” Not someone who would ever be mistaken for Steve Jobs. As discovered and described by best-selling business author and professor Jim Collins in his book, Good to Great, the Level 5 leader:

- Demonstrates a compelling modesty, shunning public adulation; never boastful.

- Acts with quiet, calm determination; relies principally on inspired standards, not inspiring charisma to motivate.

- Looks in the mirror, not the window, to apportion responsibility for poor results, never blaming other people, external factors, or bad luck.

Given the greatness of Apple under Steve Jobs’ at this moment, what are to we to make of the Level 5 leader paradigm? How quickly times, and leadership fads change!

Profound Piece of writing