In the first part of our interview, “Openness and Clarity are Overrated,” Professor Eric Eisenberg re-made the case he had pioneered as a young communication scholar in the mid-1980s when he argued against the then prevailing view inside and outside of academia that clarity and openness were the primary criteria for assessing the effectiveness of communication. Instead, he suggested, and continues to suggest, that ambiguity and even selective disclosure could be important elements in successful organizational communications.

In this, the second part of our interview, Professor Eisenberg argues that strategic ambiguity is a necessary balance against the current demands for transparency, even while recognizing the ways in which the language of ambiguity, “plausible deniability” and selective disclosure has been used to mask ethical lapses, fiduciary irresponsibility and outright malfeasance.

Dr. Eisenberg is now Professor of Communication and Dean of the College of Arts and Sciences at the University of South Florida, author of over 70 academic articles (many of which were collected in his book, “Strategic Ambiguities,”) and is working on the 7th edition of his highly-rated textbook, “Organizational Communication: Balancing Creativity and Constraint.”

Our discussion took place at The Communication Leadership Exchange Annual Conference in Atlanta, Georgia in early May 2012.

Strategic Leadership Communication:

Your examples of ambiguity in political language [in Part One of the interview] raise the specter of those who have used ambiguous language to provide cover for unethical or even criminal behavior, for example, using the concept of “plausible deniability,” which allows various miscreants to claim innocence after the fact. Doesn’t the abuse of ambiguous language make the case for clarity, openness and perhaps even the radical transparency embodied in something like WikiLeaks?

Eric Eisenberg:

There’s no doubting the contemporary hue and cry for transparency (see, for example, leadership scholar Warren Bennis’ Transparency: How Leaders Create a Culture of Candor.) And for good reason. It’s very much a corrective against backroom dealings, lying and misrepresentation.

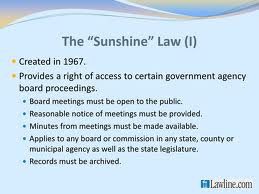

I can give you a very specific example from my own experience. In Florida, in the U.S., we have what is probably the most restrictive Sunshine Laws in the nation, which open up almost all state-supported activities to the public. So, when we [at the University of Southern Florida] do a search for a new president, or dean, or provost—a new leader for the university—all the meetings and all the notes are completely open to the public. Or when we put faculty up for tenure evaluation or promotion, the letters from those evaluating them are open to the candidates and potentially, even to the public.

That’s the kind of openness and transparency people have asked for, but in reality, it has all kinds of negative, paradoxical consequences. In our case, we’ve seen people stop speaking candidly in meetings; a lot of good candidates won’t apply for those jobs or withdraw their candidacy; and some people will refuse to write letters of recommendation if they have anything negative to say, making it hard to get honest appraisals.

Strict transparency inadvertently winds up highlighting an important need for strategic ambiguity: relational sensitivity. You don’t want to go on record as saying “X” about someone you know if you also know that everybody in the world is going to see what you have to say.

Strategic Leadership Communication:

It sounds as if you’re saying that the push to openness and clarity has had the paradoxical effect of increasing secrecy and silence?

Eric Eisenberg:

That’s exactly what I’m saying. It’s the equivalent of demanding that your partner in a marriage know everything about you because a healthy marriage is one where you have no secrets. But the fact of the matter is that’s not how human relationships work. A really healthy marriage, or any really healthy relationship has to have a balance between disclosure and protection, between expressing everything and protecting some confidences. In other words, between ambiguity and transparency.

Strategic Leadership Communication:

A last question on the concept of on strategic ambiguity: In my experience, most successful senior executives know when they need to be ambiguous. In their actual practice, they probably wouldn’t disagree with your statement that the “overemphasis on clarity and openness in organizational communication is… not a sensible standard or a widely held value against which to gauge communicative competency or effectiveness.” Nonetheless, an ethos of clarity in communication continues to exist at even the highest corporate levels. Why the strength of values and beliefs that equate clarity and openness with communication effectiveness, even when those values are not necessarily practiced?

Eric Eisenberg:

I think there are two separate things happening, and I think people conflate them; they put them together. The one thing that’s happening is that people really, really resent the abuses of power associated with secretiveness and obfuscation. As a consequence, every story in the news about an organization making some sort of ethical lapse or worse always propels people to say, “You know what? If you had a more transparent or open culture—a culture where other people knew what people were doing—this sort of thing wouldn’t have happened.” So that’s pushing from one side.

From the other side, you have an enormous amount of research and practical leadership experience that says that effectiveness in communication comes from saying just enough to make things happen, but not saying so much, or being so clear, that it forecloses all kinds of other possibilities and options.

Here’s an analogy that might help: strategic leadership communication—leadership communication that is effective—is more like giving someone a compass than it is like giving someone a map. Leadership focused on clarity is like giving someone a map: “Let me tell you the exact route to get from where you are now to where I want you to go.” The problem is that once you do that, people get passive, disengaged, or even resistant. They respond, whether overtly or not, by saying, “Wait a second. I got a brain in my head. What are you saying?”

And of course, if you lay things out with too much clarity and specificity, you run the risk of really being wrong. After all, a lot of the intelligence about what works in an organization doesn’t reside in the leader’s head; it’s widely distributed throughout the organization. If you don’t tap into that distributed intelligence, you increase the changes of making dumb, or at least difficult-to-execute decisions.

A leader who gives a compass on the other hand, says in effect, “Here’s the direction I want you to go in, and here’s the kind of metrics I’d like to see at the end. Now you go figure out the best way to chart your course.” That leaves the interpretive space for someone to make executing the strategy their own and to engage with it.

A leader who gives a compass on the other hand, says in effect, “Here’s the direction I want you to go in, and here’s the kind of metrics I’d like to see at the end. Now you go figure out the best way to chart your course.” That leaves the interpretive space for someone to make executing the strategy their own and to engage with it.

So, another paradox: too much clarity, too little engagement.

Smart leaders leave an interpretive space for people to be able to maneuver; they balance transparency with ambiguity. That balance is the hallmark of effective organizational communications.